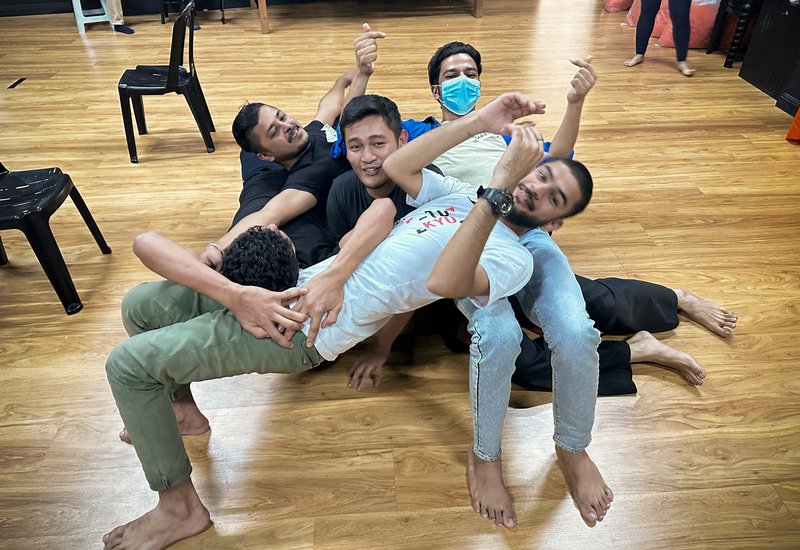

Storytelling in Malaysia. Photo Credit: GAiA Creatives

As part of MIDEQ’s Impact Initiatives, the MIDEQ Malaysia team worked with GAiA Creatives and North-South Initiative to organise a series of video workshops for Nepali migrants working in Malaysia.

This blog was authored by Okui Lala and Foo Wei Meng, from GAiA Creatives.

Storytelling & Video-making Together! was an initiative undertaken by the MIDEQ team in Malaysia to explore using more creative approaches to engage a small group of Nepali migrant workers in living in Malaysia to share their experiences. Around 20 migrant workers participated in a series of video storytelling workshops. The sessions were designed to gradually build rapport, trust and teamwork among the participants and the project team through three stages of engagement. The workshops and meetings happened once or twice a month on Sundays over one year (November 2022 - October 2023). These workshops culminated in a community screening for migrant communities and NGOs in the Klang Valley, Malaysia. The screenings provided space to share the process and outcomes of the project.

All videos made by participants can be viewed here: https://www.youtube.com/@StorytellingVideomaking2gether/playlists

Content: Stories of their lives

"Cook together, eat together" is a short tutorial video written, shot and edited by Nepali migrants, Mahesh, Kul, Khem, and Shyam, who work and reside in Shah Alam, an industrial zone in Selangor, Malaysia. At the start of the video, the protagonist expresses feelings of fatigue and loneliness after a prolonged day at the factory. Seeking to alleviate the burden, he extends an invitation to join in the mundane task of meal preparation to his housemates so that they can cook together. The video concludes with the group happily sharing a meal.

The video was part of a series created by the participants of our workshop, working together to make tutorial videos. The idea stemmed from a preliminary conversation with Khem during our recruitment in October 2022. While explaining the nature of our project, which involved using video as a medium to narrate the stories of Nepali migrant workers, Khem suggested creating videos to assist newcomers who are usually young and lack experience navigating daily life in a foreign country. His thoughtful suggestion resonated not only with our team members but also with the other Nepali migrant worker participants in our workshop.

The other three groups developed equally insightful videos, such as tutorials for a haircut, learning a new language at the workplace, and sending money back home. At first glance, the storyline of the video seems dramatic: a migrant worker feels depressed after being scolded by her employer and she now wishes to go home. The video illustrates the issue of language barriers, which causes difficulties in work environments. It also highlights the lack of support for the migrant workers in Malaysia where there are no official language classes provided to the migrant workers. Despite this unfavourable situation, a resolution appears in the video, “Learning Bahasa Malaysia”, where the migrant worker learns the language from her Nepali friend instead. The solutions presented in the four videos are drawn from the participants' own experiences, showcasing their resilience as migrant workers.

Process: Storytelling and video making together

“TikTok videos are made by yourself. You can do what you want to do. It can be reshot as many times as you want. For the video made in the group, everyone’s voice should be heard. Everyone can also advise how to make it, then only it can be made." - Dropati, workshop participant

This comment by Dropasti suggests that a different dynamic emereges when transitioning to video-making together. In a group setting, every participant's voice extends beyond mere contribution: it involves active participation, offering suggestions, navigating differences and discussions to create a video. Creating the credit list for these videos was not a straightforward process, with roles shifting organically based on individual interests, strengths and contributions. It also underwent adjustments to make room for everyone involved. This process challenges the notions of assigned roles, reflecting a collective effort on behalf of the participants to carry their stories forward.

The use of video as a means of community engagement is not new and can be traced back to the community video practitioners in London in the 1970s. Regionally, in Indonesia and Malaysia, video has been employed as a social change tool by community and activist organisations since the early 1990s. For this project, video was chosen as the primary output based on practical considerations such as its accessibility both as a tool (using a mobile phone to shoot) and outcome (being disseminated on YouTube) to the migrant communities.

The question of “how to engage?” formed a crucial aspect of our programme design. It incorporated a blend of participatory, collaborative and collective approaches, involving project team members from diverse backgrounds of community work, visual arts, theatre, education, project management and video production. Throughout the project - from the making of their videos to organising a community screening and sharing session - we tried to create a conducive environment for active listening where everyone’s input and ideas are greatly valued. Various activities were utilized to overcome the language barrier and cultural gaps between participants and facilitators. These included games, mapping, video making and even eating together. The essence of our approach lies in sharing and doing things together.

Watch the video for more details on the project process

A convivial space: Building trust and understanding over time

At the heart of a project that involves a community, the priority is often to build a safe and convivial space for everyone involved. The stories shared were not one-way from the participants only: more often than not, the facilitators, coordinators, translators and others also shared their reflections. This sharing occurred formally during workshops, casually during makan-time (lunch breaks), or personally between each other. It also extended to the virtual space of our WhatsApp group and other informal times, such as Momo time, cigarette breaks, and waiting time for all participants to arrive. It is in these times and spaces that we built our language, both verbally and non-verbally, in understanding each other.

During the initial expectation check, most participants wrote “video” as their learning interest. However, one participant Mahesh wrote "How to tell [the] migrant problem?”. In our final reflection ten months later, diverse takeaways emerged, that went beyond “video” and also included “making friends” and “supporting fellow migrant workers”. This underscores the shifting perceptions over time, illustrating the project’s broader impact beyond participants’ initial expectations. Mahesh, committed from day one, became one of the scriptwriters for “Pain of Muglan”. He also introduced the term muglan with its dual meaning of a foreign land far away from home and those who left home to work abroad. His journey from posing the question "How to tell [the] migrant problem?" to actively contributing demonstrates transformative change. The nuanced use of muglan reflects his sensitivity and understanding developed over time.

As the saying goes “It takes time to know a person’’. This sentiment also underscores the importance of time in allowing trust, between the migrant workers and us, the project team, to be developed. Our participants came from different locations. Each group had a different factory shift and each individual had different social or religious commitments to juggle during their non-working hours. Throughout our one-year engagement, achieving full attendance was challenging. However, despite being tired from a late-night shift, some participants still joined at a later hour just to be together in the workshop. Over time, a foundation of patience, care and trust was gradually built. It is under such circumstances that the stories shared in this project become truly meaningful and valuable for all involved.

Building Trust. Photo Credit: GAiA Creatives

This project is made possible with support from MIDEQ’s Impact Initiatives in Nepal-Malaysia corridor and anchored in Malaysia by Associate Professor Yeoh Seng Guan (Monash University Malaysia). It was organised by GAiA Creatives in partnership with North South Initiative (community partner) and supported by Five Arts Centre (workshop venue sponsor).

Project Team (formed by GAiA Creatives):

Co-Project Lead - Okui Lala & Foo Wei Meng

Programmers & Facilitators - Ali bin Alasri, Okui Lala & Foo Wei Meng

Project Coordinator & Documenter - Chan Sing Ying

Filmmaker Experts (Mentors) - Sharon Chong Hui Chiun & Aw See Wee

Production Team - Ceramic Films

Translator & Community Coordinator - Rajbanshi Keshab Chandra

Community Coordinator & Connector - Ramesh Kumar Pajiyar