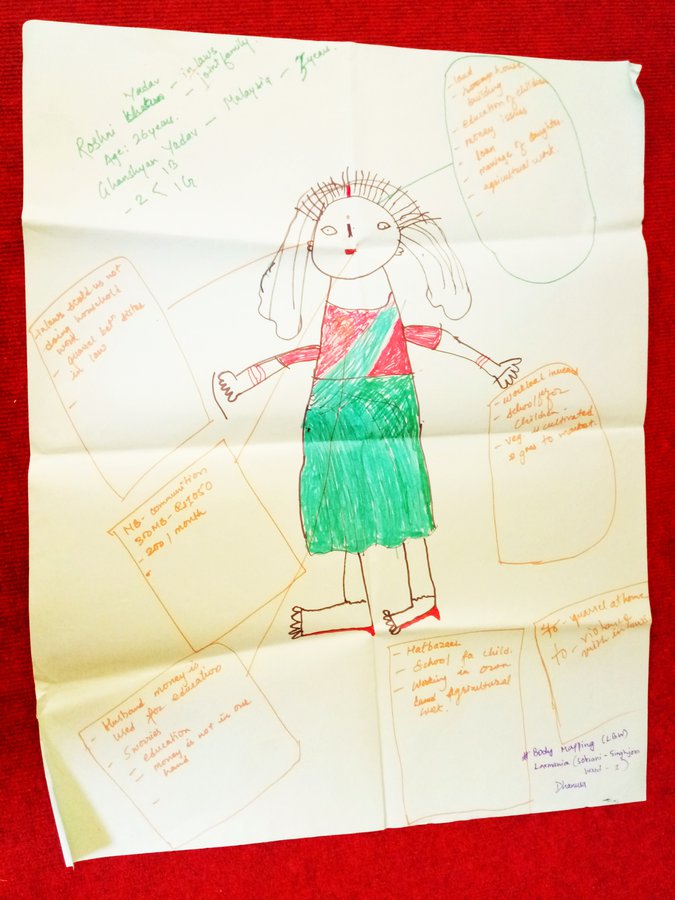

Left-behind women in Nepal sharing their experiences with challenges, support systems and aspirations after their husbands' migration. Photo by NISER for MIDEQ.

COVID-19 poses unique challenges to migrants globally. Largely, South-South labour migration does not allow for family reunification, and parents, wives and children are often left behind. Male migration in South Asia is often driven by the need to ensure the wellbeing of family members, but the impacts on the wives, ageing parents and children left behind are often negative. The adverse effects of COVID-19 on migrant workers often trickles to the family members left behind but remains largely ignored in the current mainstream discussions, which largely focuses on remittances, the impact on national economies or migrants’ welfare.

Increased economic distress for migrant families

Labour migration to the Gulf countries and Malaysia is a major livelihood strategy of Nepali people. The demand for foreign employment is strong; in the fiscal year 2018/2019 alone, Nepal’s Department of Foreign Employment (DOFE), the government body regulating foreign employment, issued 2,36,208 labour permits for aspiring migrants. This is an average of 650 people per day.

In Nepal, 56% of households receive remittances in Nepal. And migration contributed to 28% of GDP in 2018. The ADB estimates there has been a 27.8% drop in Nepali remittance in 2020. An estimated 67,000 Nepalese migrant workers have returned to Nepal during the pandemic and 60% of those who migrated 2 years ago will have returned in the next few months as their 2-year contractual visa expires. Jobs loss is significant; out of the 500,000 Nepali workers in Malaysia, 30% have lost their jobs. Loss of income and job opportunities in countries of destination is having a critical impact on these households.

Aside from a few families who had other income sources such as a small business or in agriculture, the pandemic has adversely affected if not put an end to migrant families' income. The distress on family members was clear in our MIDEQ interviews. One of the most pressing concerns for wives in this new situation was economic dependency. A majority of wives left behind have less formal education and contribute to household labor through productive (such as engaged in agriculture) and reproductive roles while not taking paid jobs. Others left-behind family members are children or older parents. Remittances from family working abroad are the main, if not the only, source of income for them. Wives and parents are accustomed to regular transfer of remittances.

Women already borrowed money from community savings – a revolving fund established in the community through monthly savings where interest rates are determined by members themselves and where members can take a loan to cope with the loss of remittance. Until they pay off the current loans, they will not get additional loans. Loss of remittances has meant they have no source to pay it. Before lockdown, it would have been paid from the remittances.

The economic and emotional impact on family left behind

Uncertainty and lack of regular information is another pressing challenge for the wives of Nepali migrants. As human beings, we crave security and like to have control over our lives and well-being and that of our dear ones. Not being in such a situation leads to feelings of powerlessness and is a source of anxiety and stress.

Uncertainty about income and whether migrants can come home back to their family has heightened. Women are fearful about the security of their husbands in destination: fear of infection but also security issues such as surveillance and potential human rights violations. The fear is not unfounded, as security and violation of rights have heightened the current situation for migrants.

For wives, news from destination countries is a constant reminder of what their spouses’ future is likely to hold. Particularly women who have lost regular connection with their husbands are experiencing double trauma; they are worried about the lack of information but also scared by news of growing infections, deaths and human right violation in countries of destinations. These fears are not unfounded: 38,034 Nepalis have been infected with the virus in various destinations and 531 Nepali migrants' workers died in the last 6 months. Reintegration is not easy: wives fear their husbands might face potential stigmatisation as COVID-19 carriers once they come back to the community.

Nepalis abroad are also feeling the impacts

The prospect of having to return empty-handed, indebted, and with no way forward has created a sense of hopelessness, longing and desperation among Nepali migrants. This anxiety is reflected in their conversation with their wives, which adds to their worries and anxiety.

In the initial days of lockdown, the husbands were strong and used to say things like, “things are fine" and that “they are carrying out their daily life well". However, as the crisis prolonged and adversity increased, Nepali migrants have started breaking down and asking families not to depend on them. For many wives in Bardiya, for example, this idea of not depending on their husband is new and unexpected, and they are unprepared for this physically and emotionally:

My husband often tells me that, it is my responsibility to look after my two daughters as he has no earnings there. Sometimes I can't control myself and start crying.

Reintegrating returnees in Nepal

After a considerable effort, the Nepal government has actively started the repatriation process. While there are challenges and gaps related to the process, after a long anxious period on both sides, migrants and their families will be able to meet each other. Whether they re-migrate or stay back will be their own decision; the government is trying to create an environment where they can exercise their freedoms and not be forced into foreign employment.

In the current budget (2020/21), the government has allocated USD 97.787 million for creating additional 200,000 jobs and is prioritising returnee migrant workers in those jobs. However, neither the wives of migrants nor the migrants themselves are aware of or actively looking for information regarding the state services and plans for migrants. This also includes services such as psychosocial counselling to deal with stress. The only support for dealing with stress is sharing with peers and neighbours who face the same challenges. This information needs to be disseminated through the local government to the people through the ward representatives.

With so many Nepali migrants returning home from working abroad, sectors such as industry, tourism, agriculture and ICT would greatly benefit from their knowledge. As a short-term intervention, the government needs to continue providing subsidies, relief, and engaging return migrants in short-term paid work. In the longer run, the central and local government should introduce social security schemes such as health and business insurance and enact strategies to encourage entrepreneurship amongst returnees arriving back with new skills.

In sectors such as agriculture, many youths in Nepal hesitate to get involved and instead would rather work abroad. Introducing tools and replacing manual work could help make the industry more youth-friendly and attractive. Migrants who have worked in agriculture in the GCC and Malaysia can also be an asset.

As the impacts of the pandemic continue to affect Nepal, individuals, communities and governments should utilize the knowledge and skills of returnees to create income-generating activities for themselves as well as for their fellow community members.